Foreword & Key Findings

Kelly Kiki

Data Journalist - Project Manager iMEdD Lab

The question of whether journalism is a vocation can be awkward for some professionals in the field –first of all, because it is often debatable what exactly qualifies as a “vocation” in general. If we are to agree that a vocation is a profession with a broad and serious social role, which one practices without being coerced and without aiming only at the size of compensation corresponding to the social commodity provided, then it may become clearer what the value basis of the question is.

Then again, what can they really say, when in reality they are practicing journalism under conditions that put their country last in the European Union in terms of press freedom and 108th in the world, out of 180 countries around the globe? Which is the response of those who work in journalism at a time it is generally acknowledged that there is a loss of trust in information and that the characterization of the media as the “fourth estate” is often used in public discourse, not to remind us that the press checks the authorities on behalf of the public, but to denounce its interdependence with them?

It would be difficult to predict with certainty the response of the journalistic community. Perhaps one could hardly expect a collective response that takes us back to our core values. And yet, the majority (71.5%) of the journalists surveyed answered positively that journalism is a vocation. In comparison, women (79%) believe it more than men (67.5%), as do younger people compared to older people, since 80% of the 17-34 age group responded positively.

The position of the sample on this question seems to be in line with the respondents’ motives for practicing the profession, since the most popular responses to this question are “I consider it to be a profession that requires responsibility and moral integrity, and I can make a great contribution to it”, “I like to inform people” and “I am motivated by the fact that I am practicing a profession with an increased social impact”.

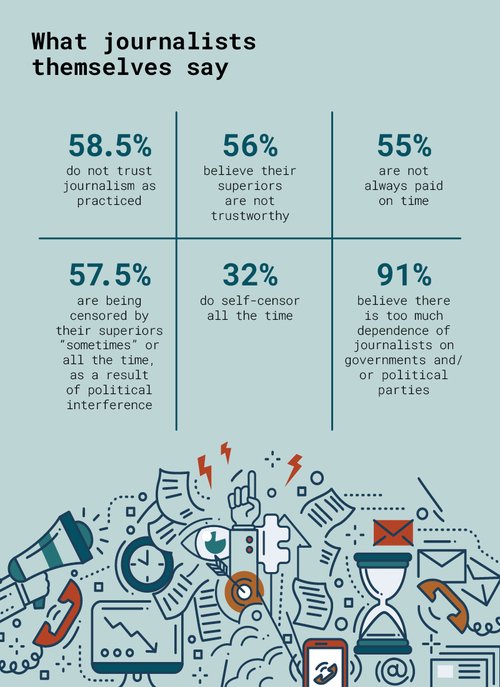

However, a divide between values and daily practice begins to emerge when participants answer more specific questions, taking into account the way the profession is practiced. Although the vast majority (87%) trust their sources, almost six out of ten journalists (58.5%) do not trust journalism as practiced. In fact, this is a view shared by all age groups and all pay scales. However, it should be noted that while the percentage of distrust is 55% among those earning more than 2,000 euros per month, it increases among the low paid: 67.5% of those earning less than 500 euros per month and 60% of professionals with a net monthly income between 501 and 800 euros do not trust journalism as practiced.

Although, of all respondents, 59% say they are satisfied with their job’s subject in their daily life, this percentage rises to 64.5% for reporters and 67% for those in staff positions (including editor-in-chief and editorial director), while it decreases to 55% for those working in a newsroom. Accordingly, 65.5% of newspaper employees say they are satisfied with their job’s subject, while this percentage decreases to 60.5% when it comes to employees of both websites and TV/radio stations.

Although the respondents are generally satisfied with the outcome of their own journalistic work (82.5%), more than half of them believe that the work produced by colleagues is not commendable (57.5%), and that their superiors are not competent (54%) and/or trustworthy (56%). At the same time, nine out of ten respondents (91.5%) believe that the public does not trust journalists.

And then one has to wonder: those who practice this journalism, which does not seem to be driven by the principle of trust on any front, how do they practice it, how faithful are they (allowed to be) to the principles of journalistic ethics and how often do they face situations contrary to their journalistic ethics?

According to responses given by survey participants, 35% do not always use sources to confirm an initial piece of information. 66% do not always check information contained in press releases before publishing it. 24% “sometimes” publishes, signed or unsigned, stories or information by colleagues in other media, without first reporting on it –and 10.5% do so regularly.

In fact, while 65.5% of those working in newspapers and 62.5% of those working in broadcasting respond that they “never” engage in this practice, the corresponding percentage decreases to 54.5% when it comes exclusively to employees of websites. At the same time, while 72.5% of reporters answer “never” to the same question, the corresponding figure drops to 49% when it comes exclusively to those working in a newsroom. 22% of journalists say they sometimes (17.5%) or systematically (3.5%) use unfair means to obtain information. 19.5% admit that they distort or withhold information, sometimes (12.5%) or systematically (7%), in order to make their story more appealing to the public. Although 91% state that they “never” deliberately publish fake news, only 65% also answer “never” when asked about the unintentional transmission of fake news.

At the same time, six out of ten participants estimate that their hierarchical superiors “sometimes” (40.5%) or all the time (22.5%) distort their journalistic work and, therefore, the journalists themselves come into conflict with them. The majority of journalists (65%) say that they are being censored by their superiors, “sometimes” (36%) or all the time (29%), for issues related to the interests or views of either their superiors or the media outlet. At the same time, 57.5% of the sample respond that they are being censored by their hierarchical superiors “sometimes” (31%) or all the time (26.5%), as a result of political interference –this percentage rises to a total of 63.5% when the analysis focuses on employees of TV and radio stations. The so-called “self-censorship” is also emerging as a major problem for the journalistic community, with 80% responding positively that they do self-censor (“sometimes”: 48%, “very often”/“always”: 32%), while 39% say they distort or withhold information because they know that their employers would object to its reporting.

The working conditions image is rounded off by three findings: firstly, 48% say that, sometimes (27%) or all the time (21%), they are afraid of losing their job because of stories they choose to cover. Secondly, eight out of ten say that, “sometimes” (47%) or all the time (32.5%), due to time pressure, they report stories or information they would have liked to have researched further. Thirdly, 55% of journalists are not always paid on time.

And, of course, it is reasonable to ask how one can defend their professional integrity when compromised: withdrawing one’s signature from the report in question, arguing and collegial solidarity/self-organized collective reaction are the most popular responses of the sample when asked about realistic ways of resisting practices of the media outlet or their superiors that are contrary to their journalistic ethics. It should be noted, however, that the percentages of those who say that they have “never” engaged in these reaction practices in the recent past are comparatively higher among younger age groups and the low-paid.

“The media serve interests and people have identified journalists with the media they work for” and “journalists have developed controversial relations with political power” are, among others, the most popular responses of participants when asked what are the factors that have caused the public to lose trust in journalists. Similarly, when asked which factors would contribute to regaining public trust, most of the respondents answer, among others, that the media need, on the one hand, “to stop being interfered with by political power” and, on the other hand, “to be more interested in journalistic content and less interested in profit and/or serving other interests”.

Besides, the section on relations between journalism and politics clearly reflects the view of the journalistic community that in our country there is too much dependence, both of journalists and the media outlets, on governments and/or political parties in general (more than 90% responded positively in each case). In fact, almost unanimously (96.5%) the sample responds that precisely this dependence has cost the public confidence, while 70.5% of journalists say that colleagues returning to the profession after having been actively involved in politics is something “problematic”.

This study, presented together with the corresponding public survey on trust in journalism, attempts a rare mapping of the opinions, attitudes and experiences of journalists themselves. In other words, it attempts a mapping of the factors that influence (their) trust in journalism –at least, as they themselves perceive, record and (co-)shape them, to the extent that corresponds to each one of them, depending on their role and choices. It would be welcome if this research could serve as a springboard for a broader discussion of (self-)critique and the search for solutions, or even to generate questions for further examination. It was with these thoughts in mind that we at iMEdD decided to undertake this research project, in view of the International Journalism Week 2022. We would also like to thank the Public Opinion and Market Research Unit of the University Research Institute of the University of Macedonia, which undertook the research and, of course, the analysis of the data presented in the following pages.